Airlines – A Soaring or Crashing Investment?

Right now, travelling is more popular than ever, as many have learned to prioritize experiences over tangible goods in the post-pandemic environment. This begs the question, should individuals get in the front seat and invest in airlines, or simply sit back and watch them take off? A QBR editor argues that despite these catalysts the industry is not poised for long term growth because of its susceptibility to exogenous factors, razor-thin margins, and abysmal historical returns.

Travelling is a hobby that is beloved by many. It is unlikely to come across people who actively dislike the idea of travelling. Despite society's broad fondness for travel, I see little appeal in investing in the underlying service which supports it—the airline industry. Airline investments are not well-positioned to soar in the long run because of their susceptibility to external factors, thin margins, and awful historical returns. Additionally, the prospect of strong returns from a short-term investment often bears too much volatility risk to justify the exposure. These factors outweigh current catalysts that linger in the public eye, such as the shift in consumer spending from goods to experiences in a post-pandemic environment. This begs the question, should people avoid airline investments, in spite their love for the service itself, and further, could airlines reshape themselves to deliver consistent returns?

Controlled by the Uncontrollable

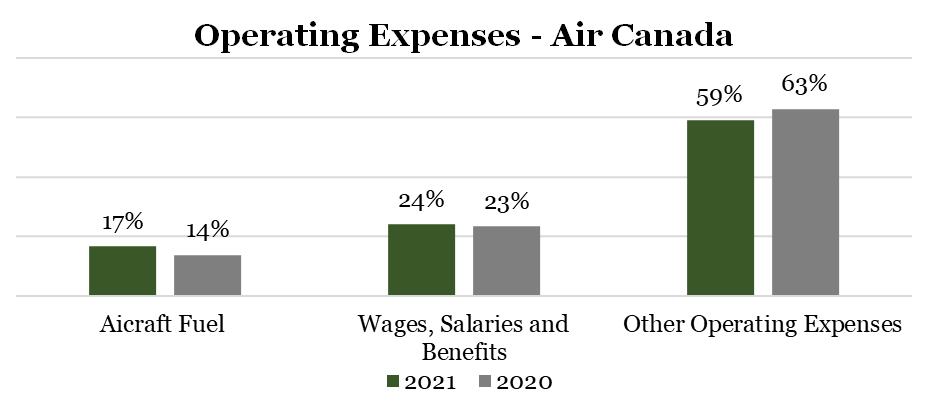

Airlines have two major costs, fuel and wages, which are heavily influenced by external factors (often rooted in the spot value of certain commodities). Oil prices constantly change with supply, demand and various macro-economic events, motivating many airlines to hedge oil prices. However, some derivatives may also fluctuate in price and will often include additional investment banking fees. For example, crude oil futures, a common hedging derivative, changed around 47 per cent between its 52-week high and low (Bloomberg). This volatility significantly affects airline profitability as it is a major cost item. According to IATA, fuel is the industry’s largest cost item, making up 24 percent of overall costs in 2022 (Oyebade, 2022). Furthermore, fuel prices are expected to remain high and volatile with supply disruptions from the Russian invasion and rapid global demand shifts.

The airline industry is also particularly prone to employee shortages and wage inflation. It struggles to attract and retain employees with extra training, security protocols, remote airport locations and an inability to accommodate a work from home model. This, along with the labor-intensive nature and unionization of the industry, makes employee shortages and wage inflation particularly pertinent. Airlines are currently experiencing these pressures with more than 5,000 flight cancellations over the Father’s Day/Juneteenth weekend (4- Morris, 2022) and unions such as Lufthansa seeking 9.5% pay rises for employees (3- Knolle, 2022). Unfortunately, history tends to repeat itself, and airlines will always continue to face employment challenges.

Exhibit 1: Segmented Operating Expenses of Air Canada in 2020 and 2021 // Source: Bloomberg

High Prices, Low Margins

These high operating costs outlined in exhibit 1 contribute to very thin and volatile margins. Although airline tickets can feel expensive for many customers, in reality, these prices are heavily pushed downwards by nature of fierce competition and minimal opportunity for differentiation in the industry, especially for international flights. In fact, the BBG World Airline Index and NYSE Arca Airline Index recorded average profit margins that were 8.31 per cent and 10.99 per cent lower than the S&P 500 over the last twenty years. The BBG World Airline Index also only surpassed the S&P 500’s profit margins once in 2015.

Furthermore, airlines are prone to significant operating and financial leverage, contributing to margin volatility . High operating leverage stems from the nature of the industry, which requires considerable capital expenditures and fixed costs (aircraft leases, machinery, insurance etc.). On the other hand, financing leverage stems from recent issuances of debt from airlines during the pandemic, which has increased debt to equity ratios for many of these firms. In September 2021 alone, airlines' short term and long term debt hit $340 billion, up 23 per cent since 2020 (6- Poh, 2021). In turn, airlines must pay high fixed costs and interest obligations on debt regardless of the revenue they generate, unlike with variable costs or dividends. This amplifies returns and profitability, often making bad times worst.

Exhibit 2: The trailing 12 month profit margin of BBG WRLD, NYSE ARCA, and the S&P 500 from September 2003 to September 2021. Source: Bloomberg

A Turbulent Past and Future

The thin and volatile margins of the industry and its sensitivity to exogenous events have contributed to poor historical returns, attesting to the risky nature of this industry. Recessions, political instability, terrorism, energy shortages and pandemics, which unfortunately will continue to occur, make airline valuations crash. In fact, passenger demand has an income elasticity ranging between 1.3 and 2.7 depending on the route and market (IATA, 2008). This means demand changes drastically with changes in consumer income and the economy, which cannot be controlled by airlines.

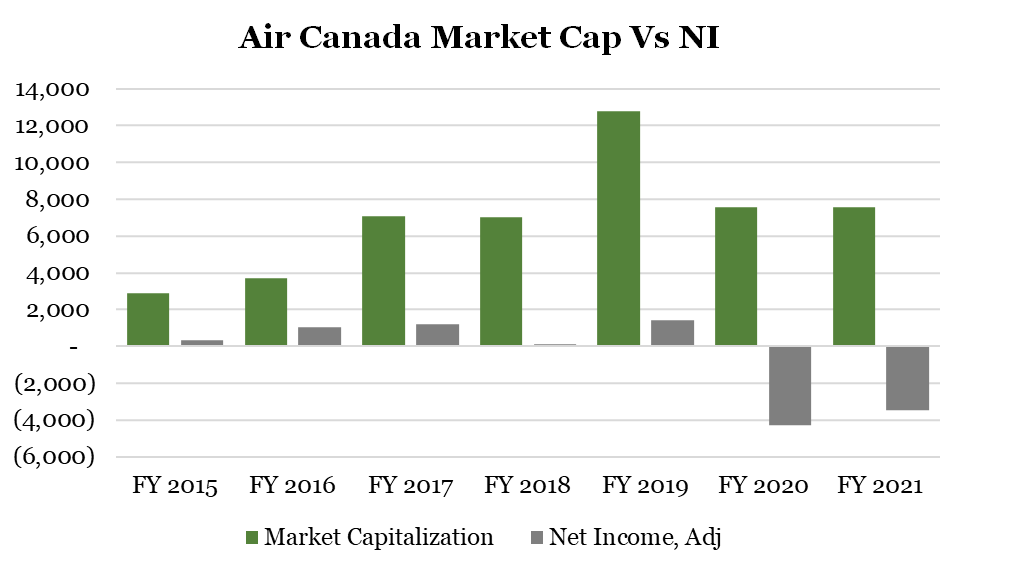

Nevertheless, many unprofitable and poorly run airlines continue to operate due to heightened stakeholder interest. This has contributed to unsound valuations. For example, in 2017, Air Canada’s market cap was ∼ $7 billion with ∼ $1.2 billion in net income. Still, in 2020 (during COVID), its market cap was around ∼ $7.5 billion with a net income of ∼ - $4.3 billion. So, Air Canada was more valuable despite being in a far worst financial position. This exhibits how market perceptions of future cash flows are unpredictable and heavily rely on government support.

Exhibit 3: Air Canada’s market cap compared to net income, from fiscal year ending 2015 to 2021. Source: Bloomberg

Even in a strong economy, airlines will often recover from the last exogenous event with an increase in debt, a decrease in employees and an inability to match the sudden spike in demand. Ultimately, airlines have a history of poor and inconsistent returns (as outlined in the graph below), demonstrating a lack of long-term upside and significant volatility. Airline indexes such as the BBG Worldwide Airline Index and NYSE Arca Airline Index recorded negative returns since 2000.

Exhibit 4: Return (%) for BBG WRLD, NYSE ARCA, and the S&P 500 since January 1, 2000. Source: Bloomberg

Sustainable long-term growth will also be a challenge for airlines. The industry is quite mature, particularly in developed countries, as it faces significant competition and slowing growth. The number of passengers enplaned and deplaned in Canadian airports have increased at a CAGR of 4.5% from 2009 to 2019 (Stats Canada, 2021). Mature companies, with a lack of revenue growth generally seek to increase margins to create shareholder value through increased cash positions; however, as outlined earlier, this will be very difficult for airlines.

Could A New Market Leader Surface?

Despite these weaknesses, an industry leader may emerge to deliver superior returns. For example, Southwest Airlines emerged as an industry leader and experienced over a 700% stock increase between its low and peak in the 2010s (Bloomberg). Southwest successfully introduced the low-cost carrier model by using inexpensive secondary airports, flying a single aircraft type to reduce training, and executing the fastest turnaround times (Bailey, 2019).

Exhibit 5: SouthWest Airline returns (%) from March 2010 to March 2019 Source: Bloomberg

A new leader could emerge by challenging the industry’s current norms to improve profit margins and lower one’s susceptibility to external factors. Potential areas of improvement include airline credit cards and fuel efficiency improvements. Airline credit cards are highly profitable because they sell miles to banks and profit from third parties with little input costs. In addition, it inherently increases flight sales and customer loyalty by forcing customers to redeem points on their flights. By gaining a dominant market position in the airline credit card market a leader can emerge with higher margins, while having a strong economic moat.

Airlines should also go beyond the ‘easy’ changes they have already made, such as essential fleet upgrades and higher seat density to minimize fuel costs. McKinsey projects that overall fuel efficiency gains for the industry will decline from approximately 3.4 percent a year to 1.5 to 2 percent unless carriers take more ambitious actions (Esqué, 2022). Advancements to replace fossil fuels and implement novel propulsion systems would help return higher and less volatile margins.

In conclusion, the airline industry is sensitive to external factors, including fuel prices, employee shortages and exogenous events, adding risk to their already thin and volatile margins. The industry has poor historical returns, suffering drastically during adverse times and falling short in a strong economy as they recover from its last adverse event. Unfortunately, disadvantageous economic conditions and circumstances will continue to occur inevitably.