Demystifying the Middle Eastern Venture Landscape

As North American powerhouses such as Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Bay Street remain idle in a rate-driven lull within the venture environment, the Middle East has emerged as the bustling VC performer with activity expanding beyond the heights of its skyscrapers. Middle Eastern startups attracted a record $3.93B in funding in 2022 and the region experienced 57 percent IPO transaction value growth in 2022 YoY, becoming the only region globally to see venture growth. Despite centuries of Western allure and fantasizing over the Middle East, Western investors fail to put their dollars behind their dreams for wealth in the region’s venture opportunities as the region remains underweight in asset allocation models relative to global competitors.

Underweight in Asset Allocation Models

For asset managers seeking global diversification, firms have the choice of applying various asset allocation frameworks when deciding how to allocate and deploy capital on an overall portfolio level across different regions and countries. Two of these main methods used in practice are GDP and share of market capitalization weighting, where asset managers will allocate capital proportionately to regions or countries based on their percentage of global GDP or market capitalization to capture its relative economic importance. Despite these asset allocation models traditionally being proven to reduce portfolio risk and variance, like all other regions, the Middle East is afflicted by Western home country bias on external investment. When compared to other regions, the Middle East fares far worse in attracting Western foreign investment when looking at venture investment, FDI, and asset manager portfolio allocations.

If focusing on GDP-weighted asset allocation, in 2021, the Middle East & North Africa (MENA) region defined by the World Bank generated $3.68T of GDP in 2021, while global GDP was $96.53T, thereby representing 3.8 percent of global GDP. On a market capitalization basis, MENA’s listed domestic companies represented $4.67T of $93.69T in 2022, representing 4.9 percent of global market capitalization. However, when normalizing to factor out the $2.1T market capitalization of Saudi Aramco which went public in 2019, its proportion of global market capitalization was 2.74 percent.

When compared to Western investment, Middle Eastern startups only obtained 0.8 percent of the $445B of global venture funding, the Middle East and all of Africa has received only 1.9 percent of U.S. FDI (32.7 percent is directed to Israel; includes energy investments) and it comprises only 0.7 percent and 0.4 percent of U.S. hedge fund and private equity portfolios respectively. Additionally, while high income Middle East countries like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, Qatar, and Kuwait might be perceived as drivers of allocation, these signs of under allocation on a GDP and market capitalization basis remain on a country-by-country level.

Qualitative Risk Factors For Underweight Allocation

While the Middle East has quantitatively received underallocation of foreign investment, investors have historically justified this on the basis of political, legal, and cultural non-alignment, regional instability, and oil dependency. These factors deter service sector investment by presenting risks to expected cash flows, thereby being reflected in discount rates and factor models. However, over the past decade, major transformations towards alignment with the West have been made in dropping legal barriers and promoting investment.

On a legal basis, a significant barrier deterring foreign investment in the Middle East was laws around foreign ownership, which traditionally limited it to over 49 percent and required local sponsors. However, in the past five years, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, and other countries have relaxed these laws to allow 100 percent foreign ownership for most industries, serving as a catalyst for increased investment interest in the Middle East. Additionally, the favourable taxation of prospective service sector ex-pats and foreign firms plays a role in attracting capital, with many Middle Eastern countries having low / no income tax and tax-free business zones today. The UAE is a regional leader in this aspect, with over 40 “Multidisciplinary Free Zones” where foreign investors side-step business barriers in traditional markets through exemptions on corporate and income taxes, customs duties, ownership regulations, capital gains taxes, and allowances of 100 percent repatriation of capital and profits. Lastly, oil dependency has declined over the past 10 years across major producing Middle Eastern countries, with oil rents falling from 26 percent of GDP to 15 percent, a prelude to the infrastructure governments have created to boost investment in service sector diversification.

Strong Ecosystem For Venture Growth

In spite of current underallocation for the Middle East, it possesses a compelling ecosystem for Western investors to back venture growth through sovereign wealth fund investment, locally specialized asset managers, and underlying secular investment catalysts.

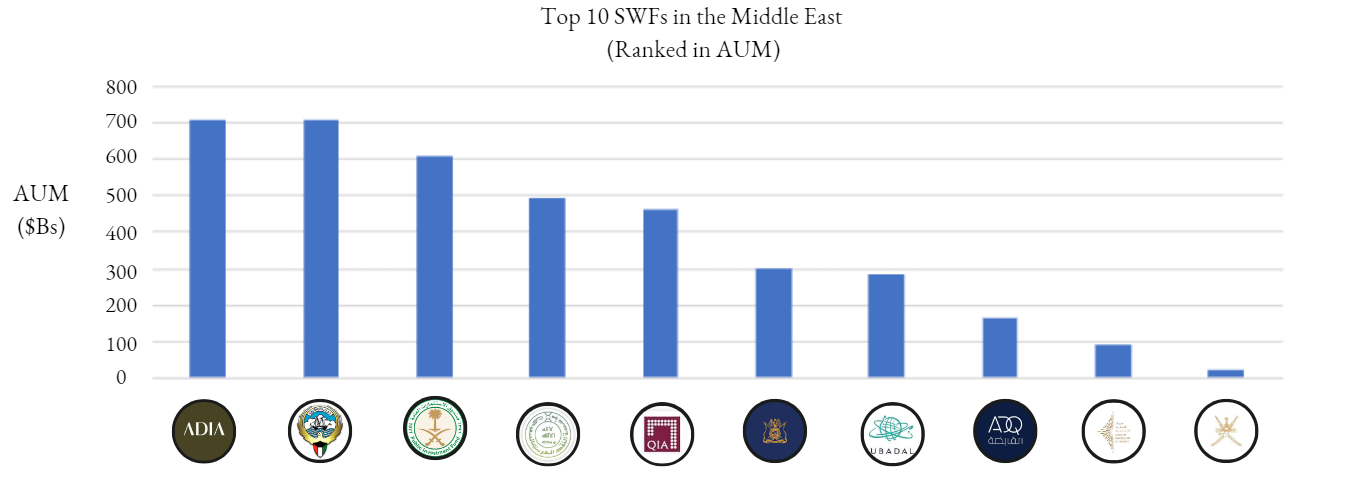

With North America’s largest diversified wealth fund being the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board with C$570B in assets under management (AUM), this pales in comparison to the scale of Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds (“SWFs”). The ten largest Middle Eastern SWFs account for ~$4T in AUM, about twice the size of Canada’s GDP, and includes the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, Kuwait Investment Authority, Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund, Qatar Investment Authority, Investment Corporation of Dubai, and Abu Dhabi Mubadala Investment Company. Most of these SWFs have globally diversified portfolios across various asset classes have mandates for local investment, thereby wielding immense influence over the business and venture ecosystem of the Middle East. Ultimately, throughout the lifecycle of prospective and realized Middle Eastern unicorns, Middle Eastern SWFs have played a major role in attracting foreign investors as these mandates to diversify local economies virtually enable a higher probability of success.

Within the lifecycle of the Middle Eastern venture environment, SWFs will rely on local venture capital funds (VCs) for sourcing investment opportunities at venture and growth stages. While these VCs don’t carry the AUM and name reputation of funds like Sequoia and Accel, major VCs like Wamda Capital, Middle East Venture Partners, RAED Ventures, and Shorooq Partners have been instrumental as incubators for SWFs and global investors to fund Middle Eastern startups. With tech unicorns like Careem, Fawry, Kitopi, and Swvl emerging from the Middle East, and pre-unicorns like Pure Harvest Smart Farms, STARZPLAY, Tamara, Sary, and Postpay, Middle Eastern VC funds have been instrumental in identifying promising ventures in Pre-Seed through Series funding, where major Middle Eastern SWFs and then international VCs have followed. With exits in previous years including Uber’s purchase of Careem, Amazon’s purchase of Souq.com, and Carriage’s acquisition by Delivery Hero, Middle Eastern ventures have proven their ability to achieve successful exits for foreign investors.

Moving forward, there are major long term investment catalysts in tech that Western investors can point towards. The Middle East’s median age is 22 years old, and the digital savvy generation has driven increased adoption of technology in the region, with 94% of the population owning a smartphone. But despite this, the digital economy remains untapped today, presenting a unique environment for tech-enabled growth where Western markets have tapped out. McKinsey has highlighted that e-Commerce penetration in the Middle East remains at 11 percent relative to 19 percent globally, only 8 percent of SMBs having an online presence, and the overall digital economy consists of only 4 percent of GDP. This is accelerated by local cultural differences that increase the difficulty foreign greenfield, enabling Middle Eastern companies that traditionally lag the U.S. in intellectual property can adopt IP to meet regional needs.

Sure, the Middle East is still presented with the struggles of regional conflicts, political differences from the West, and oil reliance. But 200 years ago, the same challenges also existed in its untapped deserts and did not limit its rise to becoming the preeminent global oil powerhouse. Today, with capital flows from Western investors and enabled by its SWFs, local VCs, and its underlying investment catalysts, the Middle East has the potential to transform its oils flows and desert valleys into another silicon valley competitor.