Injecting Transformational Optimism into The Canadian Energy Debate

In 2015, during the Paris Climate Agreement, 196 Parties at the UN Climate Change Conference – also known as COP21 – adopted an international treaty on climate change. As the gavel hit the sound block to signal adoption, cheers, and applause erupted as 5,000 people jumped out of their seats, a standing ovation for a monumental achievement.

How was this done? In the words of Christiana Figueres, the Costa Rican Diplomat who led negotiations at COP21, “by injecting transformational optimism that allowed us to go from confrontation to collaboration.”

We have seen far more confrontation than collaboration within the current Canadian discussion around climate and energy.

Climate policy has become central to the Canadian brand of politics brandished by the federal government, helmed by Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party. While the minority government has been able to pass several sweeping policies targeting emissions primarily from the energy sector, it has not come without pushback.

Climate protests occur across the nation, many of which call for the end of fossil fuels altogether. Meanwhile, in 2019, Canada’s upstream oil and gas industry employed over 500,000 people. Indigenous peoples are now seeking opportunities to gain economic prosperity from Canada’s natural resources through projects such as the Cedar LNG terminal in British Columbia and Project Reconciliation’s bid to purchase the Trans-Mountain Pipeline.

It may seem that Canada has become far too polarized to come together to work out a solution to the conundrum we find ourselves in, but there is a case to be made that injecting transformational optimism into the Canadian energy debate is just the spark we need.

Canada’s Current Energy and Climate Strategy

Canada's most recent energy and electricity data already paints an optimistic picture of what is fueling our country. However, understanding the current national energy mix only goes so far as to supply a picture of the present. The future is evident in policy, in particular, two carbon-focused policies passed by the Trudeau government: the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act and the Clean Fuel Regulations. However, these policies present associated costs to both consumers and the government.

A Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) report released in 2022 highlighted that the federal carbon pricing would cause most households to see a net loss under the government's A Healthy Environment and A Healthy Economy plan. In other words, the levy cost would exceed the Climate Action Incentive Payments meant to remove the tax burden on consumers. The report also found that the carbon pricing measure would increase the fiscal deficit by $5.2 billion in 2030-31, as the most recent federal budget projects a federal deficit of $40.1 billion in 2023-24.

Another PBO report from May of 2023 highlighted that the Clean Fuel Regulations would have a greater impact on lower-income households since they typically spend a larger share of income on transportation. The report also found that among provinces, households in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Newfoundland & Labrador would bear the highest costs of the bill due to the fossil fuel intensity of their economies.

Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Alberta challenged the federal government's "carbon tax" on the grounds that it was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled that the "carbon tax" was constitutional in 2021, but that ruling did not stop Alberta Premier Danielle Smith from calling the newly proposed federal Clean Electricity Regulations "unconstitutional and irresponsible."

While carbon pricing theoretically discourages carbon emissions, Canada's emissions levels have remained relatively steady, while our economy has grown significantly over the past two decades. Economic policy instruments such as levies and taxes may be effective but not the most efficient means of reducing greenhouse emissions. The current decarbonization and energy transition conversation primarily focuses on the domestic domain. However, if we expand our horizons and consider the bigger global picture, the case for optimism is made ever more prominent.

Global Energy Transition will Require Collaboration

On the world stage, Canada is not a major contributor to the global emissions picture. While the nation ranks as the 11th highest global emitter of greenhouse gases according to EDGAR, the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research, relative to the largest emitters, we are a blip on the radar.

The energy-GDP ratio has been revisited in research literature around economic growth. The hypothesis presumes that as one's GDP increases, so too would one's energy demands. As more nations rise out of developing to developed status in the coming decades, global emissions would be doomed to continue to increase correlative to GDP due to an irreversible relationship between energy and emissions.

This reasoning has, however, been possible to disprove by the decoupling of GDP and emissions in recent years by nations such as the United States. The United States recently reduced its carbon emissions to levels seen in the 1970s while exhibiting an economy triple the size of that time. Similar decoupling themes are present in countries such as France, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Italy, Czechia, Romania, and Canada.

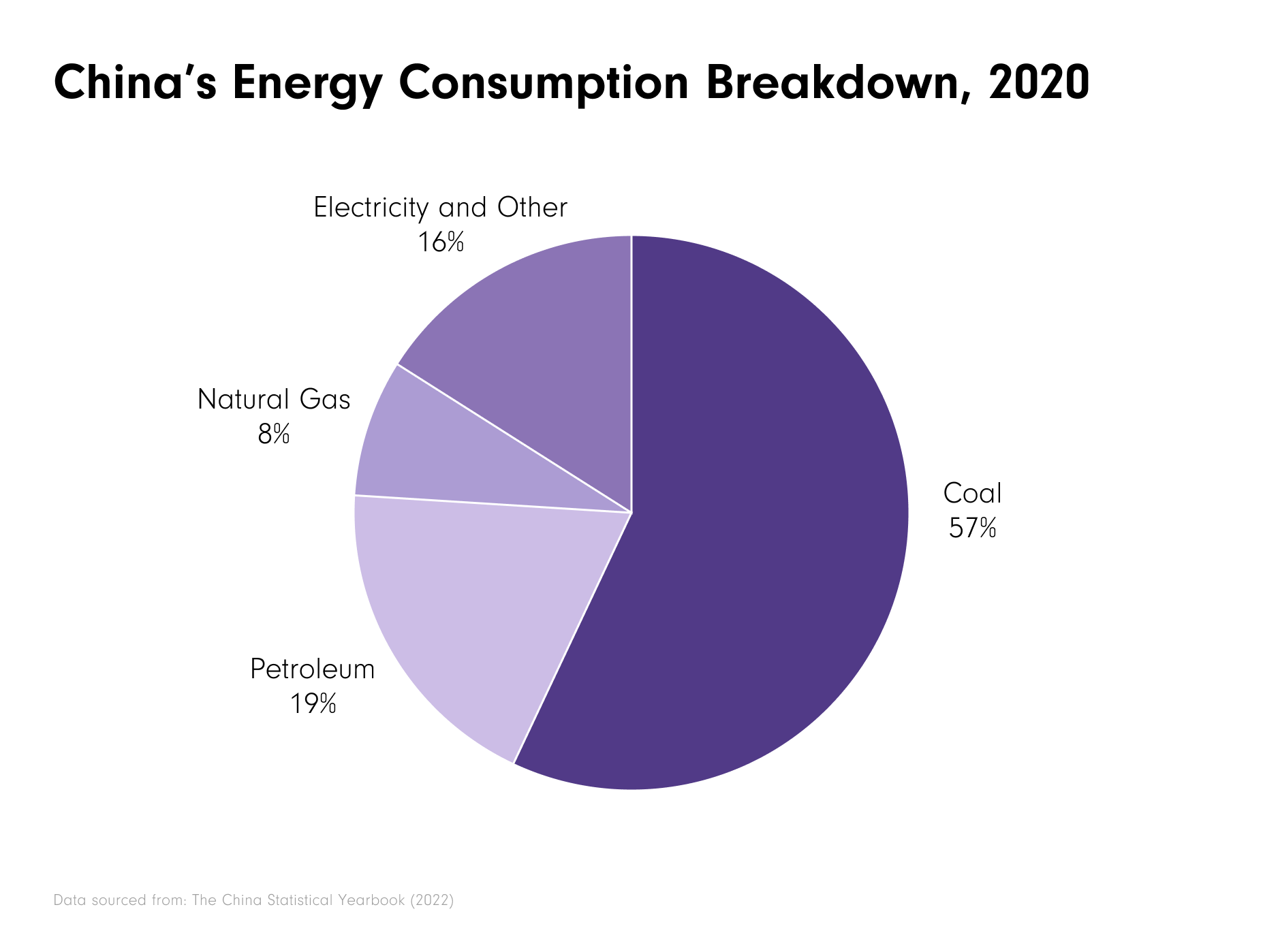

China's emissions largely stem from its current reliance on coal, which emits 50% more carbon than natural gas. Similarly, nations such as South Korea, Japan, and other countries in Southeast Asia are still substantially reliant on coal to fulfill their energy needs. Rather than vilifying these countries, it would be in the best interest of the greater world that other nations begin to establish trade relations to assist in supplying cleaner fuels, such as natural gas. Usually, to export natural gas in an economically viable manner, one must liquefy the gas, making it 1/600th its original volume. It is in the spirit of assisting the energy needs of Europe due to geopolitical instability brought on by Russia's invasion of Ukraine and East Asia's growing hunger for energy that Mexico, the United States, and Canada have all begun building LNG projects set to export to either destination.

The Case for Transformational Optimism

Going back to the beginning, the Paris Climate Agreement contains Article 6, which facilitates the grounds for voluntary carbon trading. Before recently, there was a concern about whether global carbon trading was reducing emissions due to the possibility of ‘double counting,’ which occurs when the same reduction gets counted towards achieving two different climate goals or Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

This past year, Canada’s Jonathan Wilkinson of our Natural Resources portfolio stated that Article 6 discussions were back in play, and that plans to operationalize the mechanism were at work while seeking potential LNG importers. All this comes as outlooks project Canada’s first LNG export terminal shipments to begin by 2025.

We certainly have a long way to go in reaching our global climate goals. The case for increased natural gas production and export in Canada is firm for reducing emissions worldwide. There is a valid argument that natural gas has a role as a transition fuel; natural gas is nowhere near as carbon-intensive as coal, and established policy measures exist to reduce emissions associated with natural gas production significantly. With that said, natural gas should be as stated: a transition fuel to assist the world as it transitions from high-carbon intensive fuels to a net zero future.

All aspects of the great Canadian energy debate have valid points to bring to the table, but what ultimately brings the nation together from coast to coast is widespread support for energy transition to swap a carbon-heavy energy mix for a low-carbon one. Extensive research literature corroborates this phenomenon, which is cause for tremendous optimism.

In a time where “unprecedented polarization” has become everyday jargon and where carbon perceptions are tied not to climate change beliefs but to political ideology, we must seize any opportunities to establish common ground and establish fruitful collaboration. It will be of incredible importance to Canadians to weigh multiple sides and keep an open mind as they consider what Canada’s energy strategy will look like in the coming years. The ability of our nation to come together and establish firm policies around files such as climate and energy will be one of several critical litmus tests on the functionality of our democracy.