What ESG Is and Is Not

Breaking down the investment term of the century

By 2022, 77% of institutional investors plan to stop buying non-ESG products – funds for which environmental, social, and governance factors are not considered in the investment process. Yet, based on a recent survey by State Street Global Advisors, most professional investors remain confused over ESG terminology and integration.

The absence of a standardized reporting framework for ESG data has left stakeholders to deal with the ever-changing landscape of definitions. Nevertheless, as ESG continues to make its way into boardrooms, earnings calls, and even job interviews, it is paramount to enhance the clarity concerning its taxonomy.

Without a consistent standard for reporting non-financial data, how can one navigate this space? What constitutes ESG analysis and its underlying investment philosophy? In the following discussion, we aim to better define this popular term of the 21st century. We explore some of the mainstream definitions and their implications on the investment process, with a focus on the current largest markets for ESG investments – North American and European equities.

17 Years of ESG

While non-financial considerations may date back at least as far as the 1970s, ESG was initially a term coined in a 2004 report facilitated by the UN Global Compact and the Swiss government. The initiative calls for an inclusion of ESG principles in investments to strengthen the connection between the financial sector and sustainability.

Over the years, ESG investments have achieved exponential growth as institutional and retail investors enter this arena. From 2016 to 2020, global assets under management incorporating ESG data has doubled to US$40.5 trillion, alongside a structural shift toward a more sustainable society.

Looking at the first four months of 2020, ESG fund inflows have more than doubled the volume of the previous corresponding period, despite market turbulence from COVID-19. While Toronto took a pause as it entered its second lockdown last November, the opposite is true for the sustainability movement. Canada’s big five banks committed $5 million to the Institute for Sustainable Finance here at the Smith School of Business to further Canada’s leadership in the space. The strong demand, secular growth trends, and resilience through the pandemic provide clear evidence that ESG is here to stay.

What ESG Is and Is Not

1. ESG is not an investment strategy – it is a framework.

It is not uncommon to confuse ESG integration with investment strategies such as socially responsible investing. However, by definition, it is an extension of traditional financial analysis – the incorporation of financial data like annual reports and earnings guidance. The ESG framework provides a company’s non-financial dataset that may not otherwise be captured in its financial statements. This dataset is utilized in making investment decisions across a wide array of strategies, including responsible, socially responsible, thematic, and impact investing (see Exhibit 1). It can also be used to supplement the traditional investment approach.

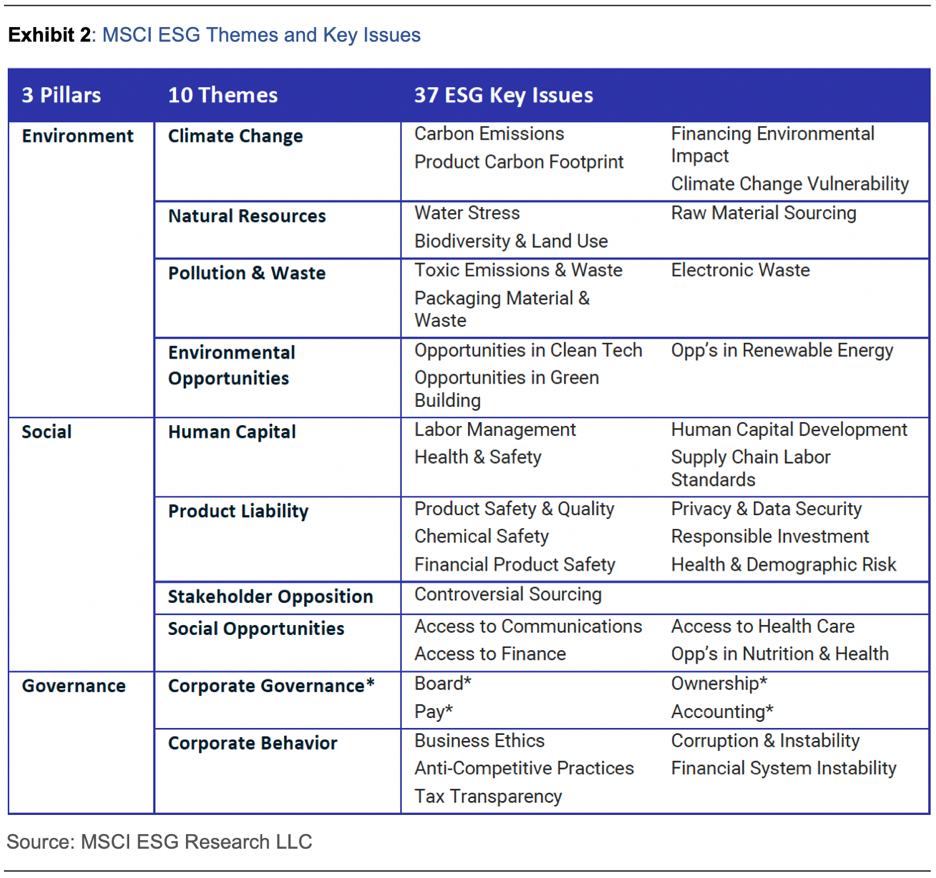

Within this framework, companies are assessed not only on their performance across environmental, social, and governance factors, but also their exposure (see Exhibit 2). The environmental pillar evaluates the firm’s contribution to matters, including climate change and pollution; the social pillar examines the impact on customers, suppliers, and communities, while the governance pillar focuses on the firm’s internal operations.

The common rationale is an economic one – these elements are fundamentally relevant to a company's bottom line and the sustainability of its business model, which can provide insights on whether it makes a good investment relative to peers. Others see ESG diligence as a fiduciary responsibility, known as the “legal duty to act solely in another party’s interests.” A 2019 United Nations report even notes, “investors that fail to incorporate ESG issues are failing their fiduciary duties and are increasingly likely to be subject to legal challenge.”

2. ESG integration is not an act of philanthropy – it is financially material to investing.

Some may examine an identical selection of ESG characteristics for every corporate issuer they are invested in. This is not quite the case. According to a study by Harvard Business School, the key is to focus on material ESG criteria. As researchers pointed out, firms with better ratings on immaterial sustainability factors do not outperform firms with poor ratings on the same factors. Meanwhile, firms with better ratings on the material sustainability factors outperform those with poor ratings. For example, carbon emissions are material to an automotive company manufacturing gas-powered cars like Volkswagen but not for a financial services company like Wells Fargo. One exception is the governance pillar, as every company needs to be well-governed irrespective of its sector.

Others may mistake ESG integration as simply an act of doing good. In reality, the material ESG factors are the risks that can “weaken or derail” an investment. Take Wells Fargo, which made headlines for a social controversy. Back in 2016, a regulator exposed the bank’s employees for opening millions of fake accounts since 2011 to meet sales targets. In addition to bad press, its stock plummeted 20% following the scandal and remained flat over the next 12 months. Just a year earlier, auto manufacturer Volkswagen was caught cheating in emissions tests with devices built in its diesel vehicles. Investors observed a 30% drop in its stock overnight and its first quarterly loss in 15 years.

On the contrary, material ESG factors can be the opportunities that enhance an investment. There is no better time to examine this lens than the early months of COVID-19 when global supply chains were put to the test. Companies with more sustainable supply chains weathered the pandemic better than those with undiversified sourcing exposure or legacy distribution models. As history suggests, ESG diligence is financially relevant to investors and not charity work.

3. ESG integration is not a standalone step within the investment process – it is an ongoing application of the framework.

ESG analysis does not represent an item on the checklist in a company initiation. Regardless of the data provider, a company’s ESG credentials only represent a moment in time. A more comprehensive view can be developed by considering its broader operating landscape, such as material shifts in the regulatory environment or physical and transition risks. At the firm-level, it is important to acknowledge the steps that companies are taking to address their ESG profile and to evaluate whether or not these are realistic goals. Hence, ESG scores are continuously assessed over the investment horizon, alongside forward-looking, qualitative inputs.

Active engagement is another component of the ongoing process. Investors can directly influence their portfolio companies to take actions that improve their ESG credentials. Engagement may take the form of proxy voting or direct conversation, although this largely varies by the investor and company situation. The “point is to express views and concerns” continuously “to those who can do something to address them,” namely the management team and board.

4. ESG ratings are not built on a one-size-fits-all weighting scheme – the magnitude is proceeded on a case-by-case basis.

The assignment of equal weightings across ESG metrics may be deemed appropriate, but in practice, it is not an arithmetic average. An investor may have a view on the relative importance of the material ESG topics for a particular sector, industry, or firm. A tailored approach would be taken to factor in systemic or company-specific matters. For example, the automotive industry has greater exposure to climate change issues than the financial services industry. On the social front, labour management is more important for businesses that engage in manufacturing like Apple than for Twitter. Accordingly, investors may place a greater emphasis on the environmental pillar and labour management for automotive companies and Apple, respectively.

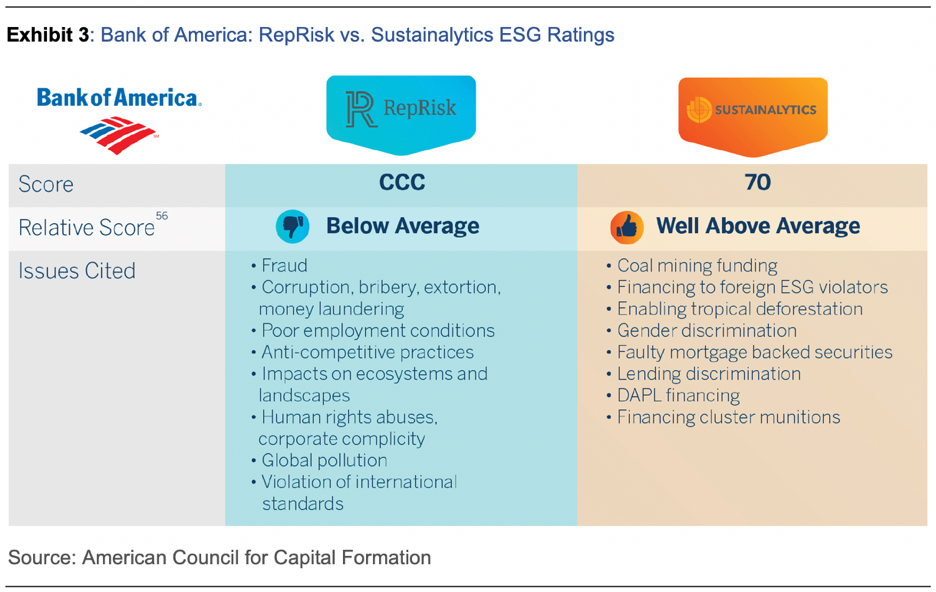

More commonly, sustainability information is retrieved from ESG rating agencies, such as MSCI, Sustainalytics, and RepRisk. Despite their expertise in ESG research, they frequently “produce conflicting ratings” when evaluating the same corporate issuer, which can be attributed to inconsistent information and the non-uniform weighting system (see Exhibit 3). This is in sharp contrast to rating agencies that employ standardized financial disclosures; for example, credit ratings from S&P and Moody’s have a positive correlation. The key here is to screen for relative ESG performance between industry peers – not absolute.

5. ESG data is not guaranteed to be complete – it is only as good as what is publicly available.

Some companies will not fully disclose their ESG data. An example is seen in smaller businesses, which may not have the same resources to devote to ESG reporting as multinational corporations. Therefore, on average, scores are positively skewed toward larger companies (see Exhibit 4). North America is another example. Firms based in this region are seen lagging behind their European peers on ESG scores, attributed to the higher quality of sustainability reporting required in the EU (see Exhibit 5). As such, these inherent biases are not to be ignored when interpreting the ratings.

Others will not self-report every ESG metric pertinent to their firm due to the non-uniform standard of disclosure. Recent developments have been made to set ESG reporting standards and the scope of materiality by institutions, such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board and the Global Reporting Initiative. Even so, there is no universal mandate to comply with these rules nor is there a stringent audit like the case for financial statements. In essence, “some ESG factors are not widely reported enough” to be sufficiently comparable for the investable universe.

The Bottom Line

ESG is a framework for evaluating a company’s non-financial information. It helps investors gauge the downside risks and economic merits across ESG factors that are material to a corporate issuer. There are shortcomings to ESG ratings and data, but the common goal of its application is to inform decision-making and strengthen longer-term investing.

I hope this discussion provides a basis for navigating the ESG framework and what it means in practice. Regulatory developments – given the white space to improve ESG taxonomy – should enhance the field over time. For now, it is important to understand what ESG is and is not, for ESG is here to stay.